In the tapestry of family life, there is no thread more vibrant or unpredictable than the literal-minded curiosity of a young child. Children exist in a world where language is a newly discovered tool, one they wield with earnest precision, often unaware of the nuances, metaphors, or private idioms that adults use to navigate their complex lives. This innocence frequently creates a comedic bridge between the mundane reality of household chores and the imaginative, sometimes surreal interpretations of a child’s mind. One such instance, now circulating as a charming anecdote of domestic life, centers on a young boy’s sudden and bizarre inquiry into the culinary potential of the power grid.

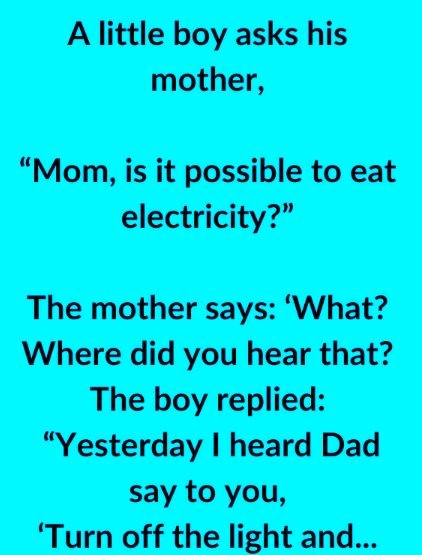

The scene begins in a typical family kitchen, a space often serving as the headquarters for both nourishment and the relentless questioning that defines early childhood. A young boy, perhaps five or six years old, looks up from his afternoon snack and poses a question that strikes his mother with the force of a lightning bolt. “Mom,” he asks with the solemnity of a philosopher, “is it possible to eat electricity?”

The mother, momentarily paralyzed by the sheer absurdity of the query, pauses her work. Her mind likely races through the various scientific and safety-related reasons why consuming an electrical current is a physical impossibility. She imagines her son might have been watching a particularly strange cartoon or perhaps misinterpreting a science lesson about “fueling” the body. Confused and slightly alarmed by the potential safety implications of a child interested in “tasting” the power outlets, she replies with a mix of bewilderment and parental concern. “What? Of course not, honey. Where on earth did you hear something like that?”

The boy’s answer, delivered with the unflinching honesty that only a child can muster, reveals the danger of the “overheard” conversation. “Well,” he explains, “yesterday I heard Dad tell you, ‘Turn off the light and put it in your mouth.’”

In that single sentence, the domestic air shifts from a lesson in physics to a moment of hilarious, tongue-tied realization for the mother. The joke, of course, relies on the child’s phonetic interpretation of a phrase that was likely far more mundane or perhaps a bit of playful, private bickering between parents that was never intended for little ears. To the boy, the instruction was a literal command involving the light—a tangible thing—and the act of consumption. He wasn’t trying to be funny; he was trying to understand the logistics of a diet that included illumination.

This story resonates because it highlights a universal truth about parenting: the “walls” in a home are never quite as thick as we imagine them to be, and the “ears” are always much sharper than we give them credit for. It is a comedic reminder that children are the ultimate eavesdroppers, processing the adult world through a filter of absolute literalism. When a father tells a mother to “put it in your mouth”—referring perhaps to a piece of food, a thermometer, or using a common, if slightly sharp, colloquialism—and couples it with a command to “turn off the light,” the child’s brain connects the two into a singular, fascinating scientific possibility. In his mind, the light wasn’t just being extinguished; it was being prepared for dinner.

The humor in this exchange is a masterclass in the “misunderstanding” trope that has fueled family sitcoms and stand-up comedy for decades. It taps into the shared experience of that “oops” moment when a parent realizes they’ve been caught saying something that requires a very creative explanation. Beyond the laughter, however, the story serves as a gentle exploration of how language evolves. For an adult, words are layered with subtext, sarcasm, and history. For a child, words are simply labels for the things they see. A “light” is a bulb that glows; “in your mouth” is where food goes. Therefore, electricity must be a snack.

In the modern digital age, where anecdotes of “kids saying the darndest things” travel across the globe in seconds, this story stands out for its simplicity and its relatability. It captures a fleeting moment of childhood that is both endearing and slightly terrifying for the parents involved. It reminds us to be mindful of our phrasing, certainly, but more importantly, it encourages us to find the joy in the chaos of raising a human being who is trying to make sense of a very strange world.

Furthermore, the anecdote touches on the concept of “domestic folklore”—the stories families tell each other at holiday dinners for years to come. One can easily imagine this boy, twenty years later, still being teased about his “electric diet” at his own wedding. The father, likely horrified in the moment the boy revealed his eavesdropping, will eventually reclaim the story as a badge of honor, a testament to the lively and unfiltered nature of their household.

Ultimately, the truth about “eating electricity” is that it is a metaphor for the way children consume the world around them. They take in every word, every gesture, and every half-whispered sentence, chewing on them until they can find a way to swallow the information. Sometimes, the result is a profound realization; other times, as in this case, it results in a question that leaves a mother speechless and a father wishing he’d been a bit more careful with his choice of words. It is a story of innocence, the accidental comedy of the home, and the enduring power of a child’s imagination to turn a dark room into a potential feast.

As the story continues to be shared, it serves as a lighthearted warning to parents everywhere: your children are listening, they are learning, and they are definitely wondering what electricity tastes like. The best response a parent can give is a deep breath, a quick laugh, and perhaps a more careful explanation of what belongs in the mouth and what stays in the light fixture.